[ad_1]

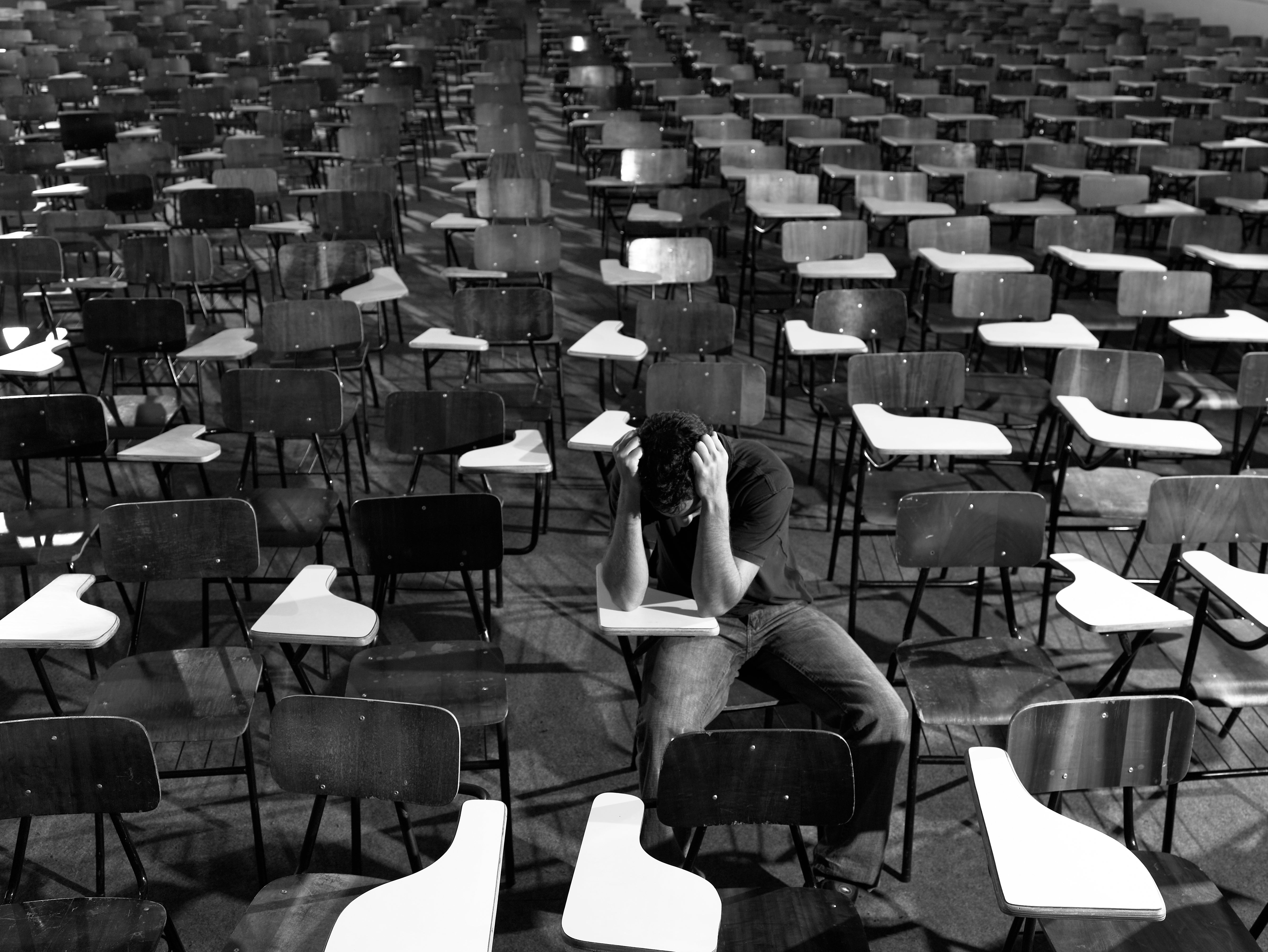

As a university scholar learning psychology, I observed school rooms in a nearby elementary university to understand a lot more about teacher opinions. On one event, an 11-calendar year-previous boy named Mark obtained a 6 out of 10 on a exam he had taken a week earlier. In response to his disappointment, the boy’s trainer reported, “It’s all right, Mark—not anyone has to be an Einstein.”

The comment caught with me. Compared with his classmates, Mark was from a reduced socioeconomic qualifications. His mom and dad have been struggling fiscally and were not able to aid him with his homework. Mark shared his bed room with his siblings, so he did not have a silent put to review at home.

Why, I questioned, did the teacher conclude that Mark wasn’t an Einstein? That comment produced Mark’s grade solely a purpose of his innate capability. Why did not the instructor think about the external conditions—such as the deficiency of a area to study—that prevented Mark from satisfying his possible?

Even properly-intentioned educators may possibly unknowingly deliver discouraging messages to young children from deprived backgrounds. In latest exploration, my colleague Constantine Sedikides, a social psychologist at the University of Southampton in England, and I have drawn on numerous research to take a look at this dilemma and have proven how these messages can develop into ingrained in children’s brain. In the system, socioeconomic inequality gets deeply etched into each child’s perceptions of themselves—with lasting and severe repercussions.

[Read more about inequality in the classroom]

Of program, most academics want to form accurate, impartial views of their students’ skills so that they can optimally tailor their schooling. But inferring a student’s ability is not straightforward. Often academics face ambiguity: a scholar may possibly do properly on some exams and inadequately on others. In those people circumstances, educators could be guided by stereotypes—generalized beliefs about a social group. A child’s gender, race and ethnicity, for illustration, may perhaps all impact the teacher’s evaluations. Socioeconomic standing may possibly do so as well. A long time of exploration locate a pervasive adverse stereotype about the mental capabilities of young children from a poorer qualifications: irrespective of their precise talents, they are commonly perceived as much less wise than other youngsters.

For example, in an experiment posted in 2021, instructors in metropolitan Lima, Peru, evaluated a 9-year-previous student who carried out inconsistently on an oral exam. The scholar acquired some difficult queries right and some simple kinds mistaken. Beforehand, each instructor viewed a person of two films introducing this pupil. The movies portrayed the child’s community and spouse and children as both middle class or bad. Even nevertheless the teachers have been ultimately analyzing the exact scholar, when they thought the nine-year-old was from a lessen socioeconomic background, they inferred that the scholar performed far more poorly, was fewer smart and was less probably to entire higher education.

That pattern has been noticed in quite a few nations around the world, together with the U.S. When this socioeconomic bias can intersect with biases towards race and ethnicity, it is obviously an supplemental impressive element that shapes children’s educational encounter. A study in the U.K. uncovered that when academics assess their students’ function, they are likely to give decreased grades to people from a poorer history, even when these pupils complete as very well as their friends. And an additional investigation—with facts from Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland—determined that lecturers are inclined to disproportionately assign learners from a disadvantaged history to reduced-stage, vocational tracks at the conclude of elementary school, even when these pupils have identical test scores and grades as their classmates.

These are illustrations of blatant bias. But in most situations, instructors specific adverse stereotypes by way of seemingly perfectly-intentioned messages and even praise. In study that I released with a colleague earlier this year, we requested 106 Dutch key school lecturers to answer to hypothetical pupils who received a higher quality on a check. The little ones have been explained in a vignette that supplied insight into their socioeconomic track record. We then coded the responses that instructors wrote and discovered that though the college students from high and minimal socioeconomic backgrounds been given roughly the exact sum of praise, lecturers lavished the pupils from a poorer background with additional inflated acceptance these types of as “Awesome! You did very well!” They did so because they assumed these learners had to work harder to realize their good results.

Nonetheless youngsters easily select up on the fundamental message. In a 2nd experiment with 63 learners aged 10 to 13 several years, we uncovered that the young ones were very attuned to teachers’ language. They inferred that a college student who received inflated praise was much more hardworking but a lot less good than other people. Consequently, even effectively-intentioned praise can boost the perception that little ones from a disadvantaged track record are much less proficient than their peers.

These inadvertently denigrating messages may well, above time, come to be ingrained in children’s mind. As I and other people have located, kids from a lessen socioeconomic history have a tendency to have extra damaging sights about by themselves. They see them selves as a lot less smart, much less ready to grow their intelligence, a lot less deserving and less worthy—even if they are as good and significant-reaching as others. The moment these self-views are proven, they continue to be rather stable across one’s lifestyle span, which suggests that kids can have these damaging concepts about their very own skill and likely into adulthood.

Self-views are consequential. Young children who maintain destructive self-sights may well avoid issues, give up in the face of setbacks and underperform under stress. As a result, their academic accomplishment suffers. Thus, as kids from a disadvantaged qualifications build more adverse self-views, they come to be fewer ready to fulfill their true probable. This signifies a tremendous loss—both for these children and for culture at massive.

Given that educators are making an attempt to enable and not damage their pupils, how does this happen? A person explanation is that in several Western countries, teachers’ pondering is generally affected by meritocracy, the thought that students’ achievements are reflections of their own merit. Faculties give all pupils the exact trainer, the similar desks and the identical assessments. The final result is the illusion of a level participating in discipline. With that seemingly equivalent starting issue, lots of educational facilities implicitly persuade the idea that college students will then realize success or fall short solely as a perform of their possess energy and ability—a meritocratic excellent. But in truth, this tactic closes teachers’ eyes to the problems college students experience outside of the classroom, these types of as no matter whether they have all the materials, options and assist desired to study and learn the materials.

In response, societies have to have to tackle the entrenched issues—such as the belief in meritocracy—that pervade our instructional system. To do so, we can endorse socioeconomic desegregation in universities and strengthen the social integration of young children from unique backgrounds. This kind of improvements would render inequality of chance additional noticeable to young children, dad and mom, instructors and policymakers. When individuals learn that college students this sort of as Mark are deprived because of their exterior circumstances, they grow to be additional supportive of insurance policies that lower inequality.

Right up until then, educators can make a real variance in their have school rooms. They can reframe students’ socioeconomic background as resources of strength alternatively than weakness. They can convey to college students that what matters is not one’s present stage of potential but how much 1 can improve around time. And they can assistance students embrace failure as an possibility for finding out. Relatively than conclude that a pupil isn’t an Einstein, teachers can assist that pupil comprehend why they bought a disappointing quality and how to do improved next time.

The author’s research described in this article was supported in portion by a Jacobs Basis Exploration Fellowship, a Jacobs Basis COVID-19 Instruction Problem Grant and an NWO Expertise System Vidi Grant. These funders experienced no position in the writing or publication of this report.

Are you a scientist who specializes in neuroscience, cognitive science or psychology? And have you read through a recent peer-reviewed paper that you would like to publish about for Mind Matters? Please mail suggestions to Scientific American’s Brain Matters editor Daisy Yuhas at [email protected].

This is an belief and analysis report, and the sights expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those people of Scientific American.

[ad_2]

Source backlink