[ad_1]

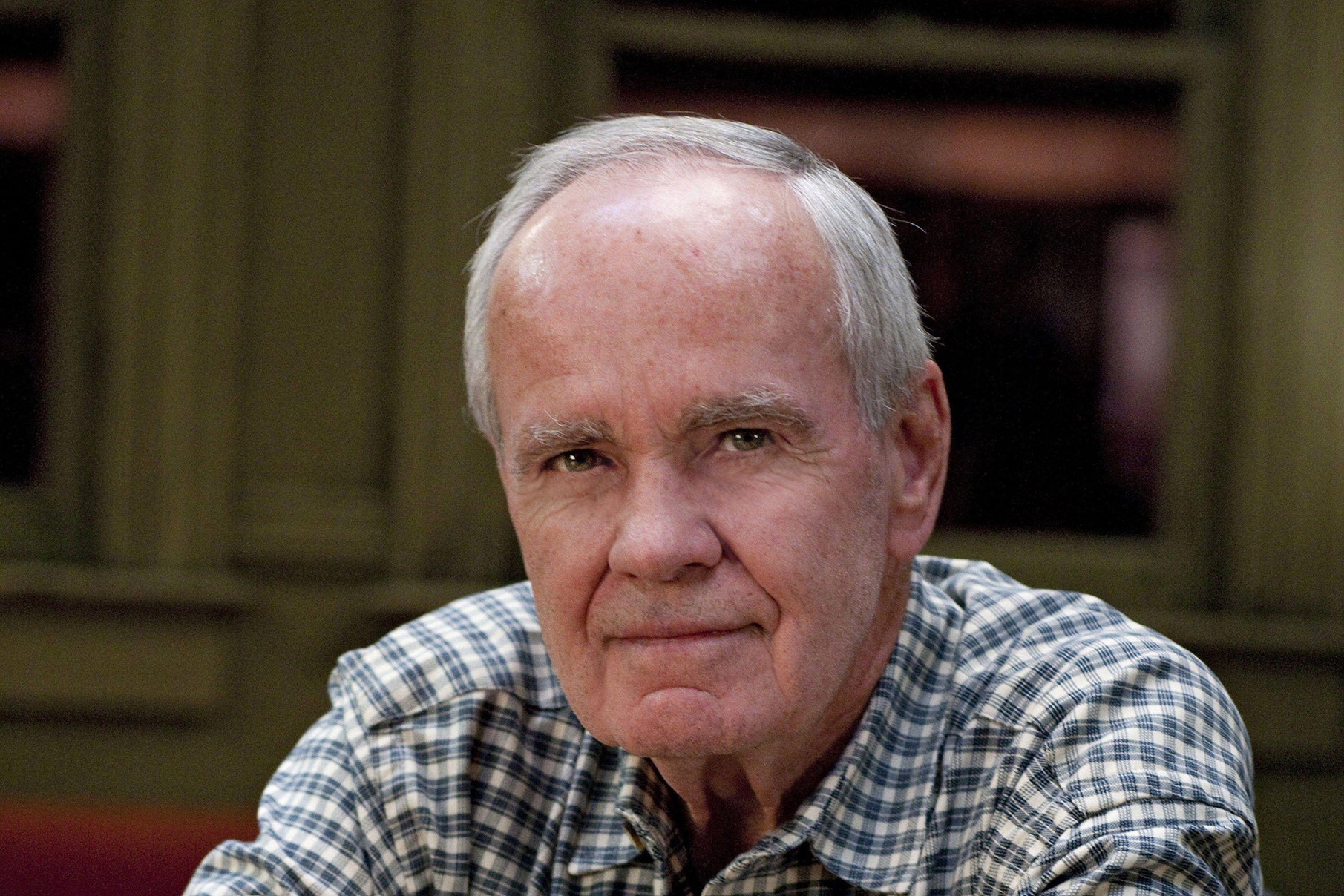

The Roman philosopher Seneca once proposed an interesting take a look at of literary advantage. “When items stand out and entice notice in a do the job you can be certain there is an uneven top quality about it,” he wrote. “One tree by alone never ever calls for admiration when the complete forest rises to the same height.” The novels of Cormac McCarthy, who died on June 13 at the age of 89, illustrate this thought that the most effective writers are persistently excellent. In the many tributes to his lyrical and philosophical gifts that have been published around the previous 7 days, what’s most amazing about the estimates from McCarthy’s novels they have bundled is just how numerous other passages could have been preferred. Even so perfect the strains one picks, robust rivals abound on each web page. Virtually all the trees are tall.

Where did these astonishing powers come from? A partial remedy is that McCarthy spent considerably of his last 3 a long time at the Santa Fe Institute in New Mexico, the analysis heart devoted to the review of complex units and big queries. There, he conversed with and befriended an eclectic team of physicists, mathematicians, biologists, archaeologists and other experts who, no matter what their unique coaching, all shared a disregard for the rigid borders of traditional academia. McCarthy, who wrote many novels on-web-site, flourished in this environment. He even wrote the institute’s running principles, a sort of polymath’s manifesto. “We are absolutely relentless at hammering down the boundaries established by tutorial disciplines and by institutional buildings,” just one sentence reads.

I met and interviewed McCarthy at the Santa Fe Institute just more than a 10 years back though creating a tale about its rare mental ecosystem. McCarthy, who usually avoided publicity, was prepared to chat 1 early morning in the institute’s library. He wasn’t eager on speaking about his have existence or function, and it swiftly became distinct that the finest way to interact him in dialogue was to converse about thoughts. He was joyful to speculate on how the unconscious mind powers unexpected insights, to parse particulars from the biography of George Washington he experienced just completed and to talk about the merits of numerous historic Greek philosophers.

There are two fundamental methods to see McCarthy’s deep curiosity in subjects further than literature. One is as a charming eccentricity primarily unrelated to his novelistic prowess. Leo Tolstoy played chess James Joyce played the piano McCarthy read through and talked science. Most likely these are just enjoyable bits of trivia—writers are an eclectic bunch with all sorts of hobbies and enthusiasms.

The other, a lot more plausible view is that his nonliterary interests are a profound clue to unraveling his function. Perhaps they are both equally the supply and material of a great deal of his fiction. Without the need of McCarthy’s omnivorous scientific curiosity, the distinct sensibility of his novels would not exist. This is unmistakable in his last two guides, The Passenger and Stella Maris, in which a significant character is a mathematical prodigy, and the nature of consciousness is a central concept. But it is equally real of lots of of his other novels. No Country for Aged Men is inconceivable with no the arithmetic of probability in its coin toss motif sundry scientific expertise offers the character of the choose his demonic omniscience in Blood Meridian the biology of wolves enriches The Crossing and a lyrical inventory of the flora and fauna of the Southwest helps make the landscape a dominant character in The Border Trilogy.

In The Passenger, McCarthy describes a significant university science fair job on pond ecology undertaken by his despondent hero, Bobby Western. “He’d drawn daily life measurement every obvious creature in that habitat from gnats and hellgrammites by way of the arachnids and crustaceans and arthropods and nine species of fish to the mammals, muskrat and mink and raccoon, and the birds, kingfisher and wood duck and grebes and herons and songbirds and hawks….Two hundred and seventy-3 creatures with their Latin names on 3 forty foot rolls of design paper.” What Bobby did for a pond, McCarthy did for whole locations and landscapes: he realized the names of almost everything in Latin, Spanish and English. This understanding gives his prose a poetry born of precision. Undergirding all the rhetorical exuberance is a diamantine core of precision.

Science is also a resource of both of those the bleak fatalism and the Platonic idealism that operate through his fiction. The study of deep background and geologic time informs the quintessential McCarthy conviction that, as the brilliant heroine of Stella Maris suggests, “The globe has created no residing issue that it does not intend to wipe out.” However nearly as sure as the triumph of demise is the presence of a partly discernible actuality that transcends issue. Describing an early mathematical epiphany, the similar character states of equations: “They had been in the paper, the ink, in me. The universe. Their invisibility could hardly ever discuss from them or their getting.” Though mortal and limited, people have some accessibility to abiding truths. We can perceive some of reality’s deep, invisible structure. McCarthy spent approximately 6 a long time crafting fiction that hovers on the verge of transcendent insight. He generally strove to disclose a far more excellent approximation of a little something true.

When we spoke in Santa Fe in 2012, McCarthy made apparent that he admired Aristotle, whose encyclopedic treatises ranged from physics to logic to ethics to biology. But he observed in Plato’s blend of literary and philosophical depth a rarer achievement. Aristotle was intriguing and systematic, but he hardly ever made anything with the remarkable richness and depth of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. This, he mentioned, was worth any number of scientific treatises.

It is uncomplicated to see McCarthy as a type of Plato among the the Aristotles of the Santa Fe Institute. For all the virtues of systematic investigation, the poetic and metaphysical splendor of his myth-making prose can compress the surprise of dozens of scientific texts into a one luminous vision. The substantial trees in his fiction improve from the soil of science.

[ad_2]

Source hyperlink